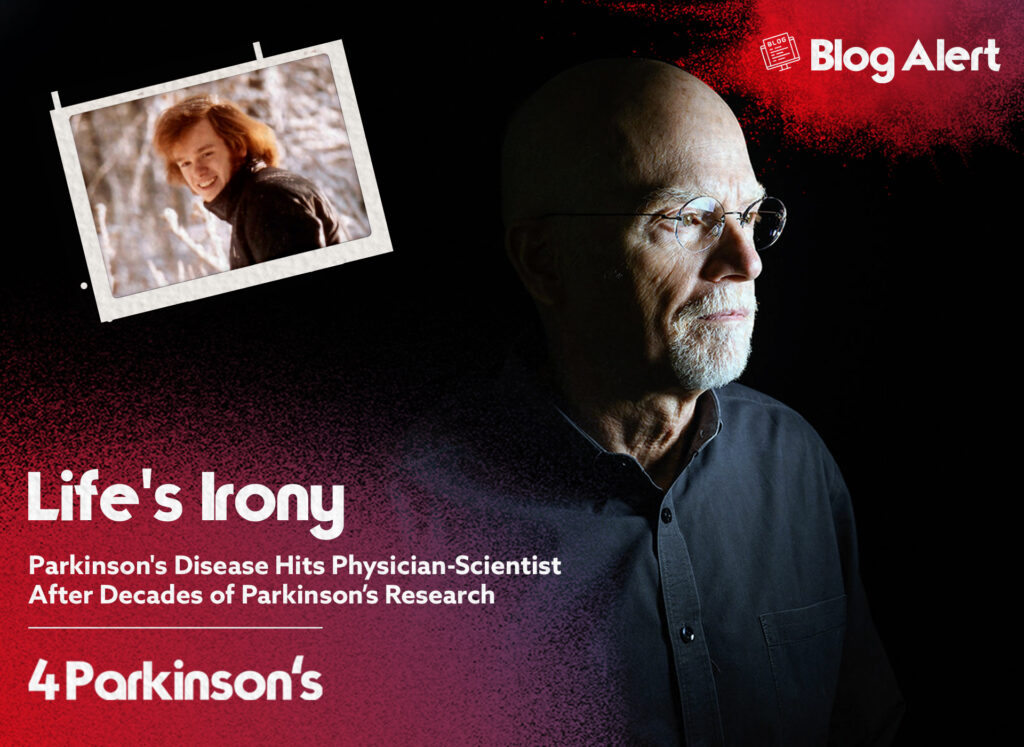

In a cruel twist of fate, decades of dedicated research on Parkinson's disease have led a prominent physician-scientist, Tim Greenamyre, to face the illness he has devoted his life to unravelling and fighting against. This poignant story unveils the irony of a lifelong quest for answers that ultimately brings the devastating reality to his doorstep.

Neuroscientist and physician Tim Greenamyre, who leads the Pittsburgh Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases at the University of Pittsburgh, has been struck by a devastating diagnosis. Several years ago, he began experiencing unsettling symptoms in his own body, including loss of smell, constipation, disruptive sleep patterns, and a lack of arm swing while walking.

Greenamyre sought help from his colleague Edward Burton, a neurologist specialising in Parkinson's disease. Burton, who has a keen eye for subtle movement abnormalities, noticed Greenamyre's slow response to a question and observed other physical signs, such as asymmetrical gait and reduced arm swing. After conducting motor tests, Burton diagnosed Greenamyre with Parkinson's, providing some relief from worrying about a more severe condition. Starting dopamine therapy rapidly improved Greenamyre's symptoms, confirming the diagnosis.

As their interview ended on that summer day in 2021, Greenamyre extended his hand to shake Burton's, expressing his gratitude. "Thank you for evaluating me," he said sincerely. Then, reflecting on the situation, Burton remarked, "Tim has demonstrated remarkable dignity and composure throughout this journey."

Despite dedicating his career to treating and finding a cure for Parkinson's, his extensive research using animal models and exploring environmental triggers may have exposed him to chemicals contributing to his illness.

"The irony is quite apparent," remarks Greenamyre, a reserved individual with a subtle wit and a fondness for pranks, who outwardly exhibit minimal, if any, visible symptoms of the disease. He mentions that, currently, medication is providing him with assistance.

Paradoxically, Greenamyre's diagnosis comes at a time of optimism for Parkinson's research, as scientists believe they are making progress toward treatments that could slow or stop the progression of this widespread neurodegenerative disease. With around 1 million affected individuals in the US and approximately 90,000 new cases diagnosed annually, Parkinson's is a rapidly growing neurological condition worldwide.

Parkinson's disease, first described by British surgeon James Parkinson in 1817, is characterised by the degeneration of dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra, a midbrain region involved in movement control. The classic motor symptoms of the disease include tremors, muscle stiffness, and problems with balance and coordination. As the disease progresses, individuals may have difficulty speaking and initiating movements. Many later develop dementia. While Parkinson's is not fatal, complications, particularly aspiration pneumonia due to difficulty swallowing, often cause death.

The combination of levodopa (L-Dopa) and carbidopa, an oral medication, has been a leading treatment since its approval in the 1970s in the United States. However, it is not available or accessible to many people worldwide. The medication improves motor symptoms but gradually loses effectiveness over time, often leading to intolerable side effects, including involuntary and sudden movements called dyskinesia. Fifty years later, the inability of science to produce a treatment that stops the disease rather than targeting its symptoms has been painful and frustrating for patients and their families.

The ageing population in the United States has contributed to a significant increase in Parkinson's prevalence. Still, the approved treatments currently available only target symptoms rather than the progression of the disease.

Inspired by a 1983 Science paper, GREENAMYRE began studying Parkinson's disease and its connection to mitochondrial damage. Among the inhibitors of complex I, a crucial mitochondrial enzyme, rotenone stood out as a classical pesticide. Using radiolabeled rotenone, Greenamyre mapped its effects on the brain, finding that it selectively destroyed dopamine-producing neurons and led to Parkinsonian symptoms in rats. This work provided the first animal model capturing both motor symptoms and hallmark pathology of the disease, raising suspicions about pesticide triggers.

After years of studying rotenone and similar compounds, GREENAMYRE questions whether his research could have been a factor in causing his illness. “Because we didn’t know as much, we weren’t as careful,” he says. “And I got exposed to things, and particularly rotenone, quite a bit.”

Greenamyre focuses on understanding the mechanisms that lead to the destruction of neurons in Parkinson's, particularly the interplay between genes and the environment, including the effects of pesticides and solvents. His research has shed light on how mutations in genes like LRRK2 can contribute to Parkinson's, and he has also investigated how environmental toxins can mimic the effects of these mutations.

In one study led by postdoc Briana de Miranda, Greenamyre's group found that the solvent trichloroethylene, used in dry-cleaning and metal degreasing, increased LRRK2 enzyme activity and induced Parkinson-like pathology in the brains of older rats. This research has implications for a class action lawsuit related to trichloroethylene exposure. Greenamyre's work on environmental toxins has also played a role in a lawsuit against the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regarding the reapproval of the herbicide paraquat, which has been linked to Parkinson's disease.

After years of managing 200 patients, it was then becoming one.

Almost all of Greenamyre's approximately 200 Parkinson's patients, some of whom he has been caring for over a decade, will become aware of his diagnosis through this article, as he reluctantly makes his condition public due to rumours circulating. However, he is concerned that it will divert their attention. "I want their visits to be centred around them, not me," he says.

Greenamyre chose not to disclose his diagnosis to the patients he interacted with that day, but he later sent them an email to ensure they were not caught off guard when the information became public. “I told him he was in my thoughts and prayers,” says Maskiewicz, who has been Greenamyre’s patient for nine years. “And I offered to chat, ‘If you ever just want somebody to talk to’— because sometimes that’s the difficult part of this disease.”

Joining the conversation via Zoom from Florida, Robert Hannan, an 84-year-old retired CEO of a drugstore chain, shares his experience as another patient. Having battled Parkinson's disease for 25 years, he now relies on L-dopa medication every two hours. However, as the effects of the drug wear off, he encounters slurred speech and the return of tremors in his left hand.

Similar to the millions of other individuals affected by Parkinson's, Greenamyre's patients share the anticipation for advancements beyond dopamine treatment. One patient expresses their hope: “Each time I visit, I inquire, 'Is there a promising breakthrough on the horizon?

To learn more about the topic, check out the article 'A version of this story appeared in Science, Vol 380, Issue 6644'.

Join our community in spreading hope and strength. Tell us your unique journey with Parkinson's to uplift and empower others.